Richard Lindzen and many others have long maintained that climate science promotes alarm in order to secure funding. For example:

Regarding Professor Nordhaus’s fifth point that there is no evidence that money is at issue, we simply note that funding for climate science has expanded by a factor of 15 since the early 1990s, and that most of this funding would disappear with the absence of alarm. Climate alarmism has expanded into a hundred-billion-dollar industry far broader than just research. Economists are usually sensitive to the incentive structure, so it is curious that the overwhelming incentives to promote climate alarm are not a consideration to Professor Nordhaus. There are no remotely comparable incentives to the contrary position provided by the industries that he claims would be harmed by the policies he advocates.

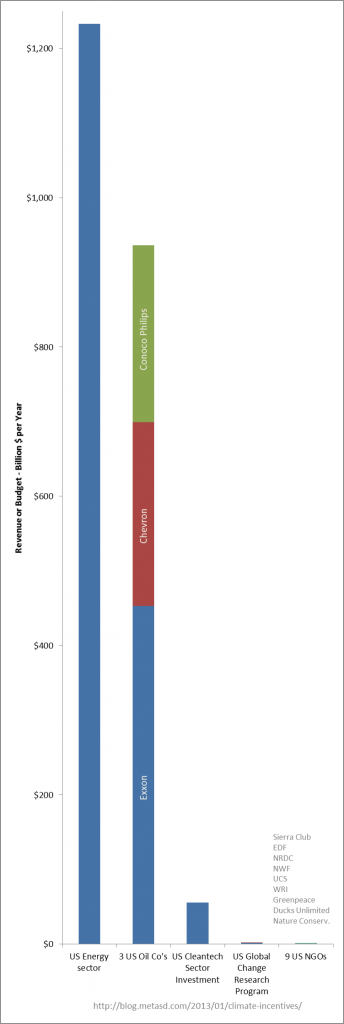

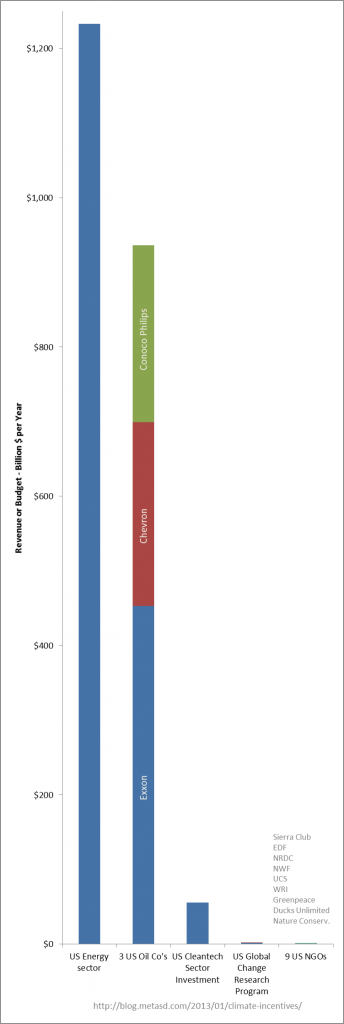

I’ve always found this idea completely absurd, but to prep for an upcoming talk I decided to collect some rough numbers. A picture says it all:

Data

Notice that it’s completely impractical to make the scale large enough to see any detail in climate science funding or NGOs. I didn’t even bother to include the climate-specific NGOs, like 350.org and USCAN, because they are too tiny to show up (under $10m/yr). Yet, if anything, my tally of the climate-related activity is inflated. For example, a big slice of US Global Change Research is remote sensing (56% of the budget is NASA), which is not strictly climate-related. The cleantech sector is highly fragmented and diverse, and driven by many incentives other than climate. Over 2/3 of the NGO revenue stream consists of Ducks Unlimited and the Nature Conservancy, which are not primarily climate advocates.

Nordhaus, hardly a tree hugger himself, sensibly responds,

As a fifth point, they defend their argument that standard climate science is corrupted by the need to exaggerate warming to obtain research funds. They elaborate this argument by stating, “There are no remotely comparable incentives to the contrary position provided by the industries that he claims would be harmed by the policies he advocates.”

This is a ludicrous comparison. To get some facts on the ground, I will compare two specific cases: that of my university and that of Dr. Cohen’s former employer, ExxonMobil. Federal climate-related research grants to Yale University, for which I work, averaged $1.4 million per year over the last decade. This represents 0.5 percent of last year’s total revenues.

By contrast, the sales of ExxonMobil, for which Dr. Cohen worked as manager of strategic planning and programs, were $467 billion last year. ExxonMobil produces and sells primarily fossil fuels, which lead to large quantities of CO2 emissions. A substantial charge for emitting CO2 would raise the prices and reduce the sales of its oil, gas, and coal products. ExxonMobil has, according to several reports, pursued its economic self-interest by working to undermine mainstream climate science. A report of the Union of Concerned Scientists stated that ExxonMobil “has funneled about $16 million between 1998 and 2005 to a network of ideological and advocacy organizations that manufacture uncertainty” on global warming. So ExxonMobil has spent more covertly undermining climate-change science than all of Yale University’s federal climate-related grants in this area.

Money isn’t the whole story. Science is self-correcting, at least if you believe in empiricism and some kind of shared underlying physical reality. If funding pressures could somehow overcome the gigantic asymmetry of resources to favor alarmism, the opportunity for a researcher to have a Galileo moment would grow as the mainstream accumulated unsolved puzzles. Sooner or later, better theories would become irresistible. But that has not been the history of climate science; alternative hypotheses have been more risible than irresistible.

Given the scale of the numbers, each of the big 3 oil companies could run a climate science program as big as the US government’s, for 1% of revenues. Surely the NPV of their potential costs, if faced with a real climate policy, would justify that. But they don’t. Why? Perhaps they know that they wouldn’t get a different answer, or that it’s far cheaper to hire shills to make stuff up than to do real science?