I’m working on Chronic Wasting Disease in deer in a couple US states. One interesting question is, what have historical management actions actually done to mitigate prevalence and spread of the disease?

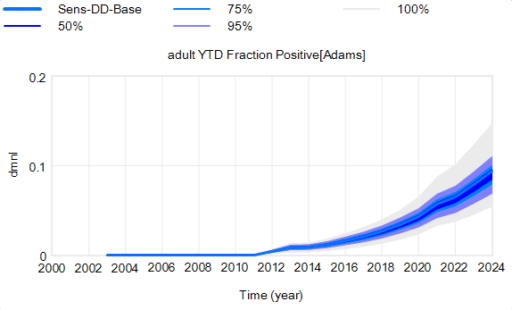

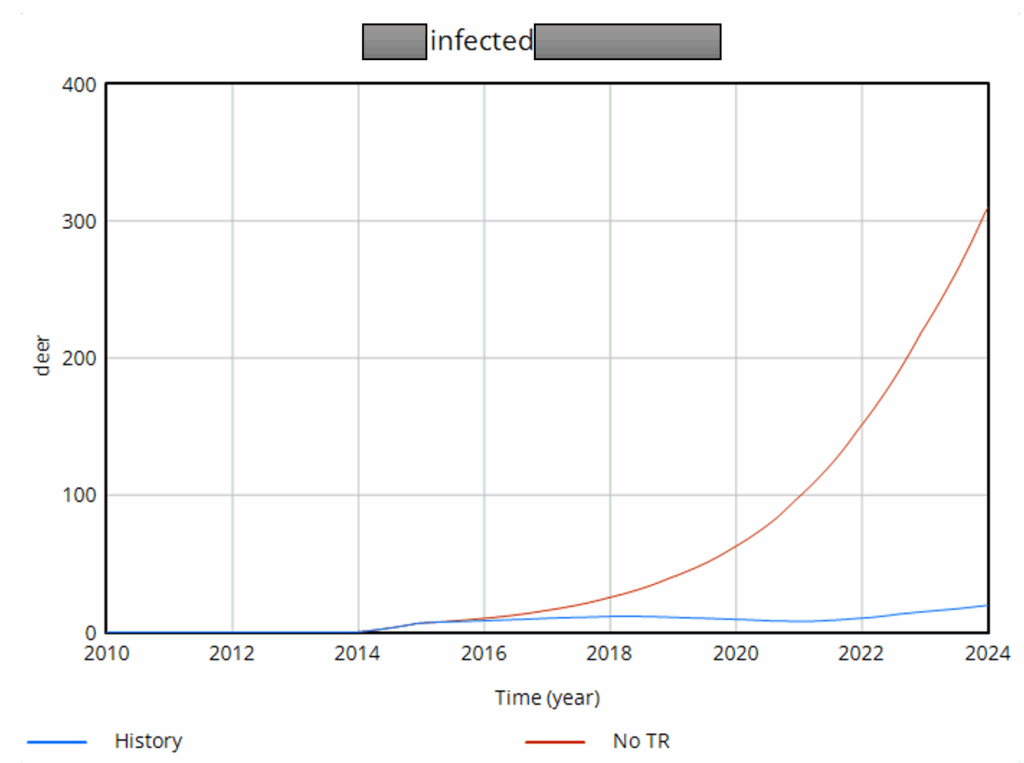

We think we have pretty strong evidence that targeted removals and increased harvest of antlerless deer (lowering population density) have a substantial effect, though not many regions have been able to fully deploy these measures. Here’s one that’s been highly effective:

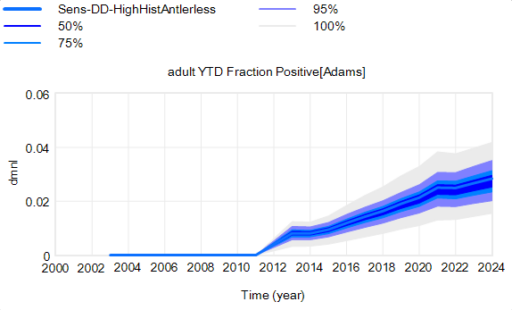

… and here’s one that’s less successful, due to low targeted removal rates and a later start:

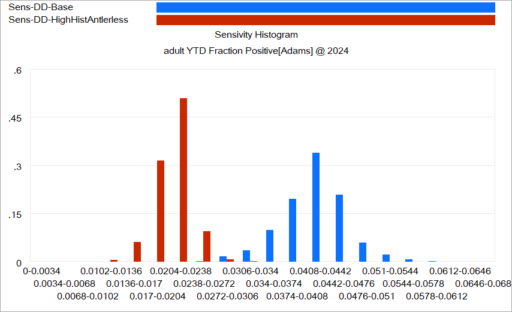

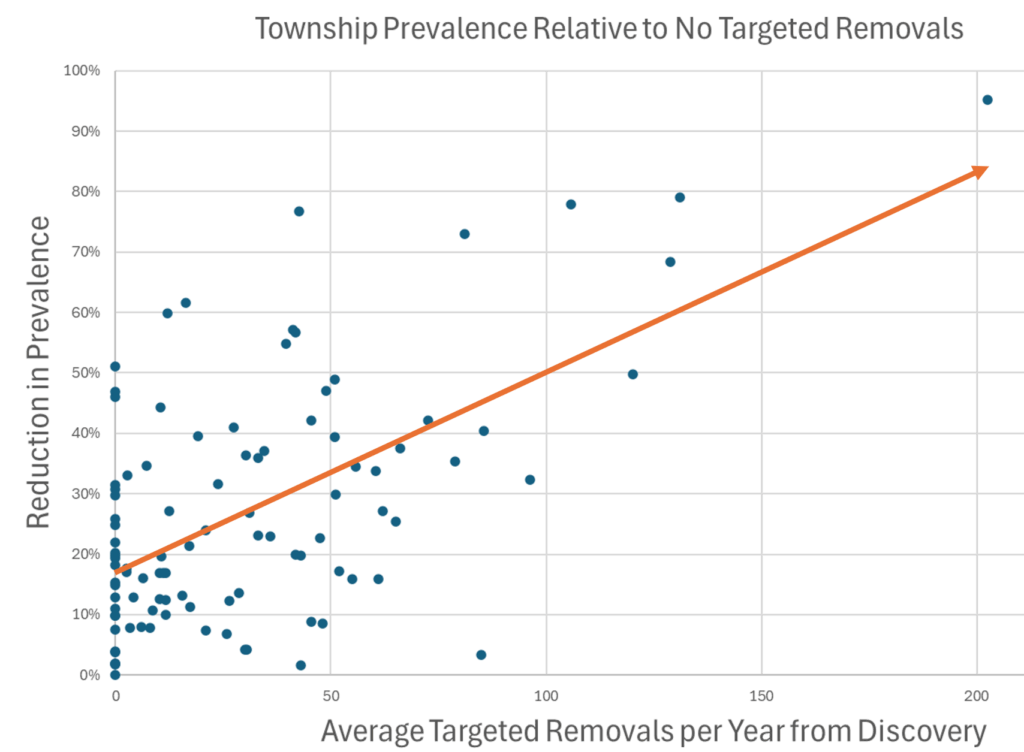

When you look at the result across lots of regions, there’s a clear pattern. More removals = lower prevalence, and even regions that received no treatment benefited due to geographic spillovers from deer dispersal.

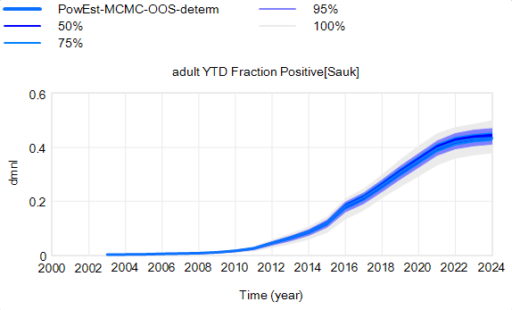

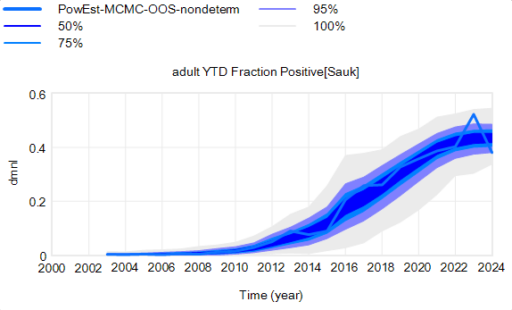

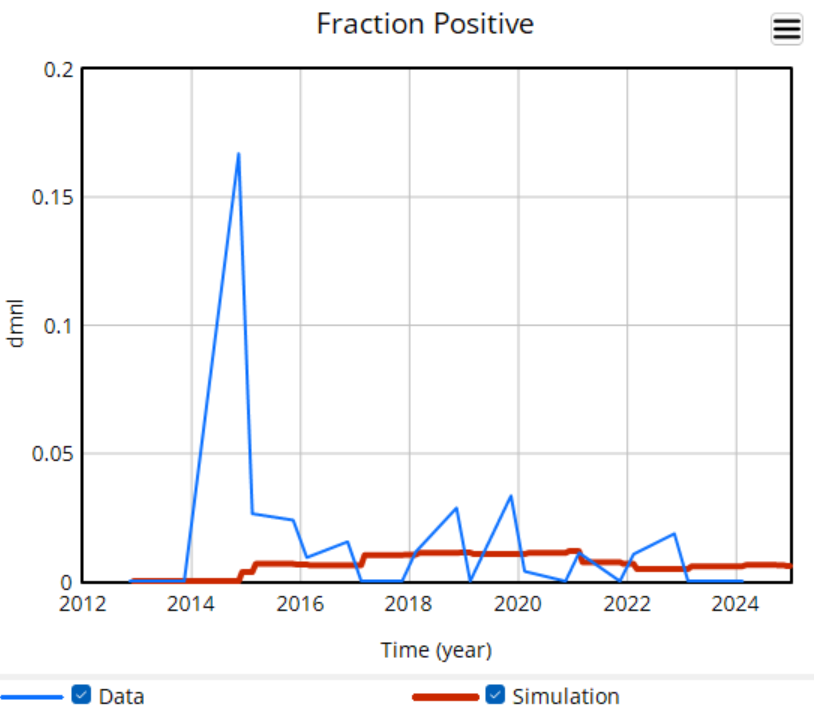

There’s a challenge with these results though: they’re all from simulations. There’s a good reason for that: most of the raw data is too noisy to be informative. Here’s some of the better data we have:

The noise in the data is inherent in sampling processes, and here it’s exacerbated by the fact that the sample size is small and varying a lot. The initial spike, for example, is a lucky discovery of 2 positive deer in a sample of 12. This makes it almost impossible to do sensible eyeball comparisons between regions in the raw data, and of course the data doesn’t include counterfactuals.

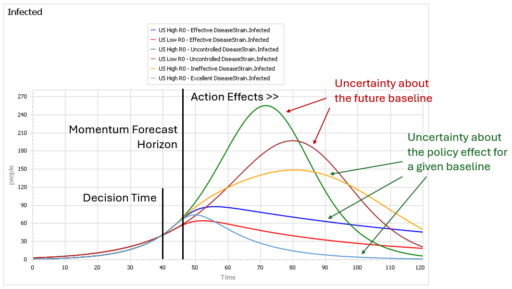

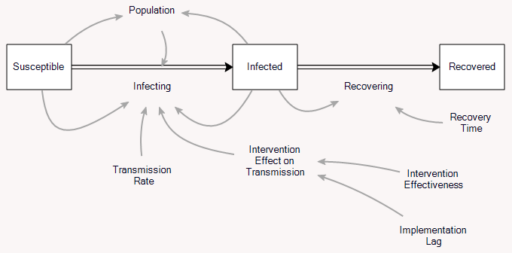

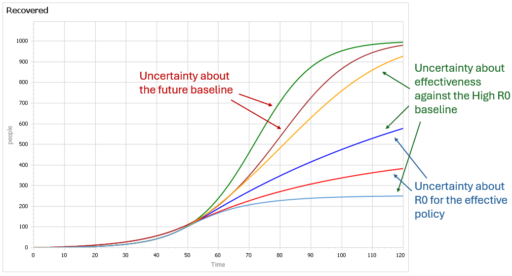

The model does do counterfactuals, but as soon as you show simulated results, you have a hill to climb. You have to explain what a model is and does, and what’s in the particular model in use. Some people may be skeptical (wrongly) of the very idea of a model. You may not have time for these conversations. So, one habit I’ve picked up from Ventana is to use the model result as a guide for where to look for compelling data that cleanly illustrates what the model is doing.

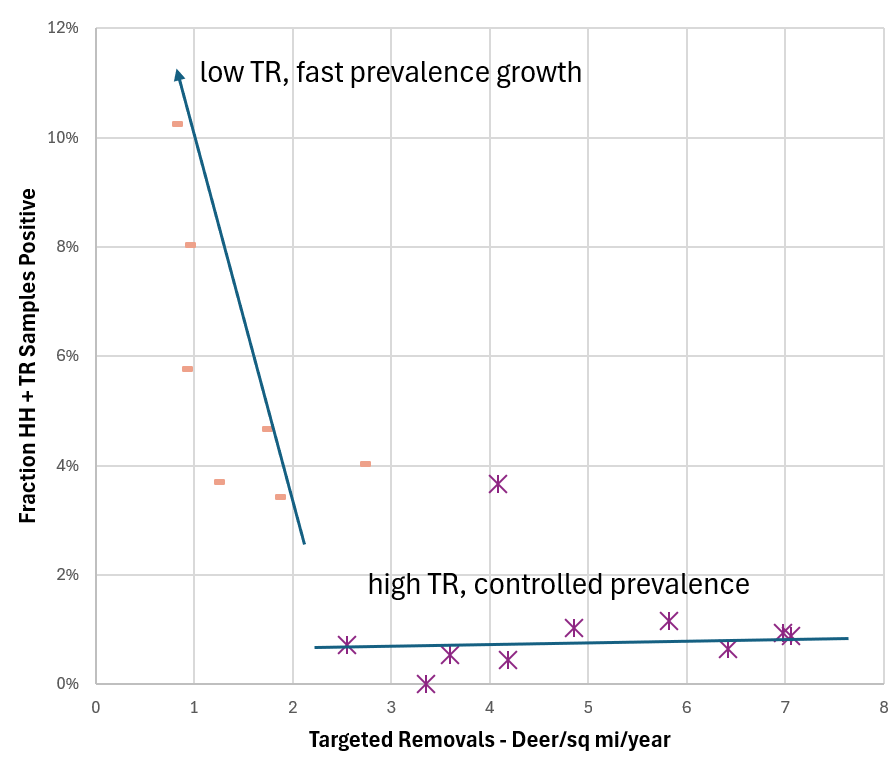

It turns out there is some in this case. Here are the histories of two regions that received different CWD management treatments, and had wildly different outcomes:

There are still some assumptions here – any interpretation of data is really a model – but I think this view is skeptic-resistant. It’s still not ideal, because scatterplots are less widely understood than time series plots, but I think it’s a useful complement to the simulation model results.