Following my big tent query, I was reexamining Axtell’s critique of SD aggregation and my response. My opinion hasn’t changed much: I still think Axtell’s critique of aggregation is very useful, albeit directed at a straw dog vision of SD that doesn’t exist, and that building bridges remains important.

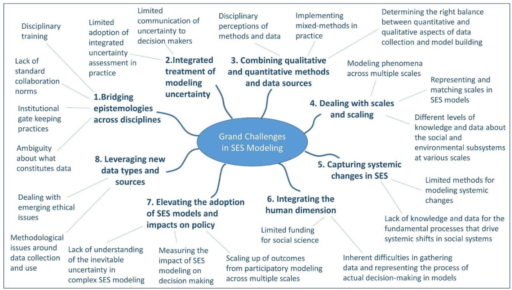

As I was attempting to relocate the critique document, I ran across this nice article on Eight grand challenges in socio-environmental systems modeling.

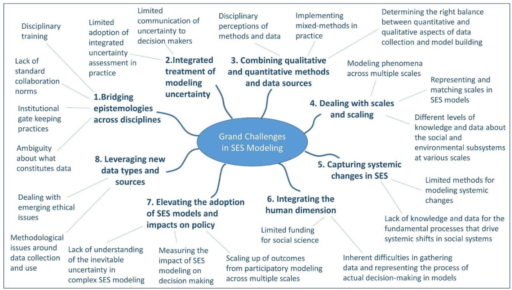

Modeling is essential to characterize and explore complex societal and environmental issues in systematic and collaborative ways. Socio-environmental systems (SES) modeling integrates knowledge and perspectives into conceptual and computational tools that explicitly recognize how human decisions affect the environment. Depending on the modeling purpose, many SES modelers also realize that involvement of stakeholders and experts is fundamental to support social learning and decision-making processes for achieving improved environmental and social outcomes. The contribution of this paper lies in identifying and formulating grand challenges that need to be overcome to accelerate the development and adaptation of SES modeling. Eight challenges are delineated: bridging epistemologies across disciplines; multi-dimensional uncertainty assessment and management; scales and scaling issues; combining qualitative and quantitative methods and data; furthering the adoption and impacts of SES modeling on policy; capturing structural changes; representing human dimensions in SES; and leveraging new data types and sources. These challenges limit our ability to effectively use SES modeling to provide the knowledge and information essential for supporting decision making. Whereas some of these challenges are not unique to SES modeling and may be pervasive in other scientific fields, they still act as barriers as well as research opportunities for the SES modeling community. For each challenge, we outline basic steps that can be taken to surmount the underpinning barriers. Thus, the paper identifies priority research areas in SES modeling, chiefly related to progressing modeling products, processes and practices.

Elsawah et al., 2020

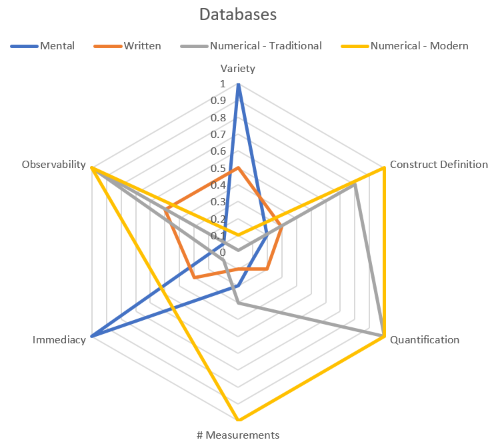

The findings are nicely summarized in Figure 1:

Click to Enlarge

Not surprisingly, item #1 is … building bridges. This is why I’m more of a “big tent” guy. Is systems thinking a subset of system dynamics, or is system dynamics a subset of systems thinking? I think the appropriate answer is, “who cares?” Such disciplinary fence-building is occasionally informative, but more often needlessly divisive and useless for solving real-world problems.

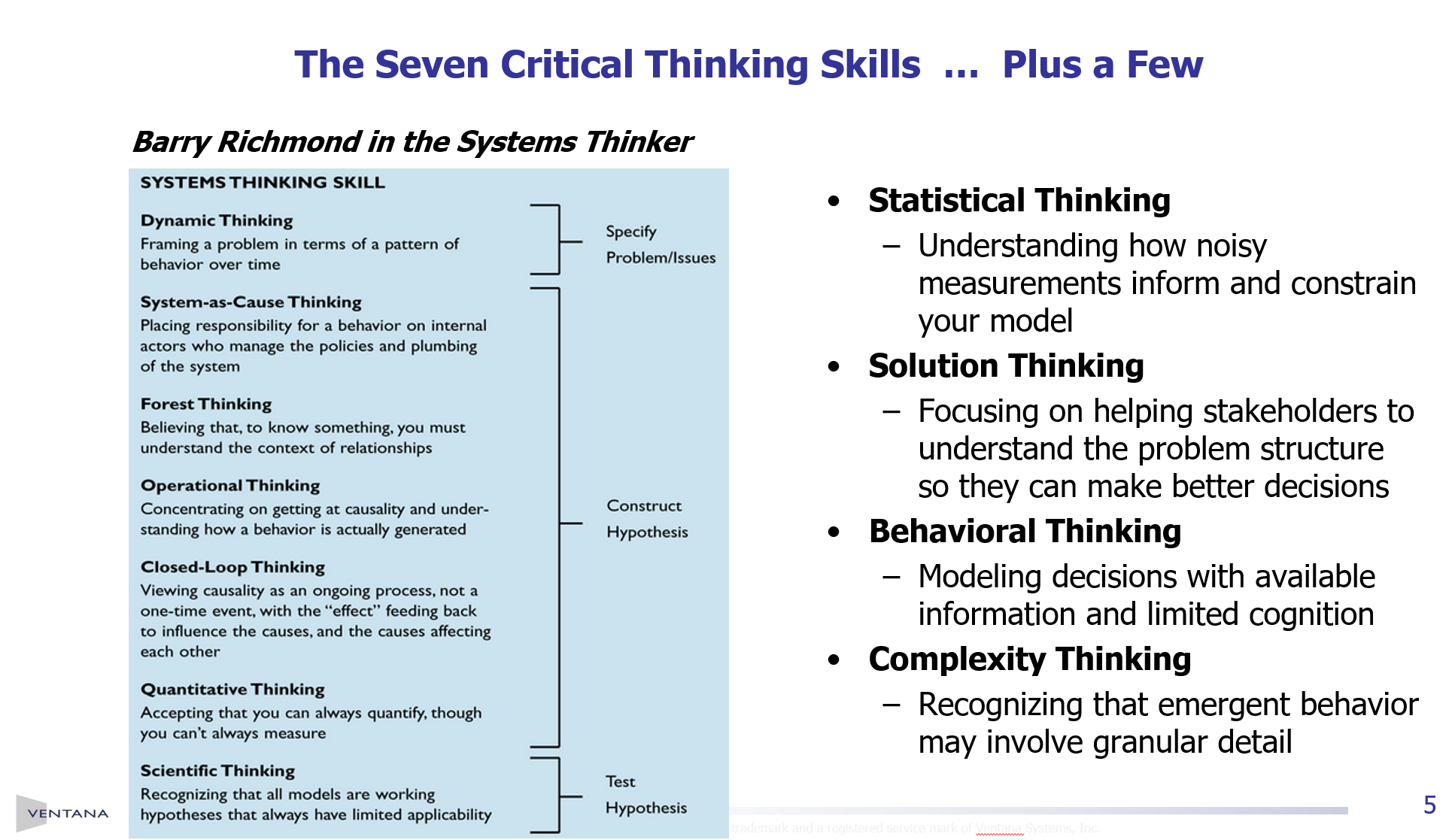

It’s interesting to contrast this with George Richardson’s list for SD:

The potential pitfalls of our current successes suggest the time is right to sketch a view of outstanding problems in the field of system dynamics, to focus the attention of people in the field on especially promising or especially problematic issues. …

Understanding model behavior

Accumulating wise practice

Advancing practice

Accumulating results

Making models accessible

Qualitative mapping and formal modeling

Widening the base

Confidence and validation

Problems for the Future of System Dynamics

George P. Richardson

The contrasts here are interesting. Elsewah et al. are more interested in multiscale phenomena, data, uncertainty and systemic change (#5, which I think means autopoeisis, not merely change over time). I think these are all important and perhaps underappreciated priorities for the future of SD as well. Richardson on the other hand is more interested in validation and understanding of models, making progress cumulative, and widening participation in several ways.

More importantly, I think there’s really a lot of overlap – in fact I don’t think either party would disagree with anything on the other’s list. In particular, both support mixed qualitative and computational methods and increasing the influence of models.

I think Forrester’s view on influence is illuminating:

One hears repeatedly the question of how we in system dynamics might reach “decision makers.” With respect to the important questions, there are no decision makers. Those at the top of a hierarchy only appear to have influence. They can act on small questions and small deviations from current practice, but they are subservient to the constituencies that support them. This is true in both government and in corporations. The big issues cannot be dealt with in the realm of small decisions. If you want to nudge a small change in government, you can apply systems thinking logic, or draw a few causal loop diagrams, or hire a lobbyist, or bribe the right people. However, solutions to the most important sources of social discontent require reversing cherished policies that are causing the trouble. There are no decision makers with the power and courage to reverse ingrained policies that would be directly contrary to public expectations. Before one can hope to influence government, one must build the public constituency to support policy reversals.

System Dynamics—the Next Fifty Years

Jay W. Forrester

This neatly explains Forrester’s emphasis on education as a prerequisite for change. Richardson may agree, because this is essentially “widening the base” and “making models accessible”. My first impression was that Elsawah et al. were taking more of a “modeling priesthood” view of things, but in the end they write:

New kinds of interactive interfaces are also needed to help stakeholders access models, be it to make sense of simulation results (e.g. through monetization of values or other forms of impact representation), to shape assumptions and inputs in model development and scenario building, and to actively negotiate around inevitable conflicts and tradeoffs. The role of stakeholders should be much more expansive than a passive from experts, and rather is a co-creator of models, knowledge and solutions.

Where I sit in post-covid America, with atavistic desires for simpler times that never existed looming large in politics, broadening the base for model participation seems more important than ever. It’s just a bit daunting to compare the long time constant on learning with the short fuse on some of the big problems we hope these grand challenges will solve.

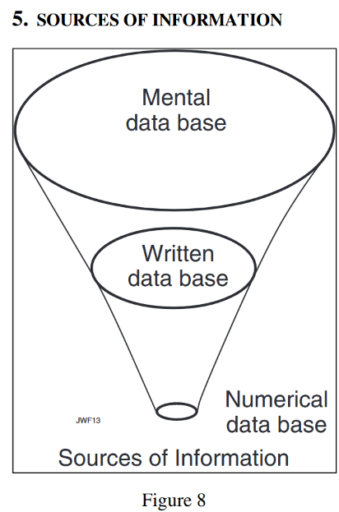

I think the diagram, or at least the concept, is much older than that.

I think the diagram, or at least the concept, is much older than that.